The confluence of the tiny San Pedro River and the a lot bigger Gila was as soon as one of many richest locales in one of the productive river ecosystems within the American Southwest, an incomparable oasis of biodiversity.

The rivers regularly flooded their banks, a life-giving pulse that created sprawling riverside cienegas, or fertile wetlands; braided and beaver-dammed channels; meandering oxbows; and bosques — riparian habitats with towering cottonwoods, mesquite and willows. This lush, moist Arizona panorama, mixed with the searing warmth of the Sonoran Desert, gave rise to an unlimited array of bugs, fish and wildlife, together with apex predators corresponding to Mexican wolves, grizzly bears, jaguars and cougars, which prowled the river corridors.

The confluence now’s a really completely different place, its richness lengthy diminished. A large mountain of orange- and dun-colored smelter tailings, left from the times of copper and lead processing and riddled with arsenic, towers the place the 2 rivers meet. Water hardly ever flows there, with an occasional summer season downpour delivering an ephemeral trickle.

On a current go to, just a few brown, stagnant swimming pools remained. In a single, tons of of small fish gasped for oxygen. An egret that had been feeding on the fish flew off. The plop of a bull frog, an invasive species, echoed within the scorching, nonetheless air.

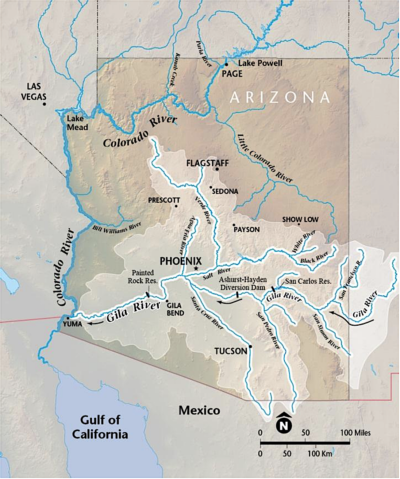

The Gila River runs from the mountains of southern New Mexico throughout Arizona to the Colorado River.

Environmental Protection Fund

The Gila River, which was listed by the advocacy group American Rivers in 2019 because the nation’s most endangered river, drains an unlimited watershed of 60,000 sq. miles. Stretches have lengthy been depleted, largely due to crop irrigation and the water calls for of huge cities. Now, a hotter and drier local weather is bearing down on ecosystems which have been disadvantaged of water, fragmented, and in any other case altered, their pure resilience undone by human actions.

Different desert rivers across the globe — from the Nile to the Tigris and Euphrates to the Amu Darya in Central Asia — face related threats. Efforts are underway to revive some integrity to those pure methods, however it’s an uphill battle, partially as a result of desert rivers are extra fragile than rivers in cooler, wetter locations.

Final yr was the second-hottest and second-driest on report in Arizona, the place warmth information are regularly damaged. The final two years have seen fewer desert downpours, recognized regionally as monsoons, an necessary supply of summer season river circulation.

“We’re coping with a quickly altering local weather that’s changing into, total, extra dry and diverse and hotter,” mentioned Scott Wilbor, an ecologist in Tucson who research desert river ecosystems, together with the San Pedro. “We’re in uncharted territory.”

Born of snowmelt and comes within the mountains of southern New Mexico, the Gila is the southernmost snow-fed river in the USA. It was as soon as perennial, working 649 miles till it emptied into the Colorado River. Because the local weather warms, scientists predict that by 2050 snow will not fall within the Black and Mogollon ranges that kind the Gila’s headwaters, depriving the river of its main supply of water.

“We’re seeing a mix of long-term local weather change and actually dangerous drought,” mentioned David Gutzler, a professor emeritus of climatology on the College of New Mexico. If the drought is extended, he mentioned, “that’s after we’ll see the river dry up.”

The Gila River because it nears the Florence Diversion Dam in Arizona was nearly dry by Might this yr.

The identical state of affairs is taking part in out on the once-mighty Colorado, the Rio Grande, and lots of smaller Southwest rivers, all going through what is commonly referred to as a megadrought. Some analysis signifies {that a} southwestern U.S. megadrought could final many years, whereas different scientists worry the area is threatened by a everlasting aridification due to rising temperatures.

Worldwide, mentioned Ian Harrison, a freshwater professional with Conservation Worldwide, “just about the place there are rivers in arid areas, they’re struggling by way of a mix of local weather change and growth.”

Just like the Gila, many of those rivers have excessive levels of endemism. “Life is commonly extremely specialised to these explicit circumstances and solely lives on that one river, so the impacts of loss are catastrophic,” he mentioned.

Rivers in all places are necessary for biodiversity, however particularly so within the desert, the place 90 % of life is discovered inside a mile of the river. Almost half of North America’s 900 or so chicken species use the Gila and its tributaries, together with some that stay nowhere else within the U.S., such because the widespread blackhawk and northern beardless tyrannulet. Two endangered birds, the southwestern willow flycatcher and yellow-billed cuckoo, stay alongside the Gila and its tributaries, together with the San Pedro and the Salt.

Desert rivers, in fact, make life within the desert doable for folks, too. Rising crops within the perpetual warmth of the desert may be extremely profitable, particularly if the water is free or practically so due to subsidies from the federal authorities. Agriculture is the place a lot of the water within the Gila goes.

A vermillion flycatcher perched close to the Gila River in Safford, Arizona.

This spring, photographer Ted Wooden and I made a journey alongside the size of the Gila, from the headwaters in New Mexico to west of Phoenix. In most of Arizona, the Gila is dry. The place it nonetheless flows, I used to be impressed by how such a comparatively small river, underneath the best circumstances, may be so life-giving. The journey introduced house what desert rivers are up towards because the local weather modifications, and likewise how a lot restoration, and what sorts, may be anticipated to guard the biodiversity that continues to be.

Our journey started on the river’s supply, the place Cliff Dweller Creek spills out of a shady canyon lined with Gambel oak in Gila Cliff Dwellings Nationwide Monument. The creek is barely a trickle right here. Above the creek, ancestral Puebloans, referred to as Mogollon, as soon as lived in dwellings wedged into caves, making pottery and tending vegetable gardens. The Mogollon deserted these canyons within the 15th century, maybe accomplished in by an prolonged drought.

From inside a Mogollon cave, I appeared out at rolling hills, lined with ponderosa pine, pinyon and juniper bushes. The green-hued water good points quantity the place three forks come collectively close to right here. Traditionally, the mountain snow melts slowly every spring, offering excessive regular flows by way of April and Might. Flows gradual to a trickle in June. In July and August, monsoons move by way of and, together with frontal methods, trigger flash flooding and an increase in water ranges.

Flooding is a “disturbance regime,” not in contrast to a forest fireplace, that rejuvenates growing older, static ecosystems. A wholesome river within the mountains of the West is one which behaves like a fireplace hose, whipping backwards and forwards in a broad channel over time, flash flooding after which receding, transferring gravel, rocks, logs and different particles all through the system. A flooding river always demolishes some sections of a river and builds others, creating new habitat — cleansing silt from gravel so fish can spawn, for example, or flushing sediment from wetlands. A river that flows over its banks, recharges aquifers and moistens the soil in order that the seedlings of cottonwoods, mesquite bushes and different vegetation can reproduce. Alongside wholesome stretches of the Gila, birds are in all places; I noticed quite a few bluebirds within the branches of emerald inexperienced cottonwoods.

Gila Cliff Dwellings Nationwide Monument New Mexico, an ancestral Puebloan break on the headwaters of the Gila River.

The riparian ecosystem that traces the 80 or so miles of the New Mexico portion is essentially intact due to the protections afforded by federal wilderness areas, the shortage of a dam, and the river’s circulation not being utterly siphoned off for farming. That is an anomaly in a state that has misplaced lots of its riparian ecosystems. “That is the final free-flowing river in New Mexico,” mentioned Allyson Siwik, govt director of the Gila Conservation Coalition.

The way forward for the New Mexico stretch of the river is unsure due to the potential for extra water withdrawals and the lack of snowpack. “We’ve seen flows within the final 10 years decrease than we’ve ever seen,” Siwik mentioned. This yr, she mentioned, set an all-time low on the river, with circulation lower than 20 % of regular.

Undammed, the Gila River by way of New Mexico nonetheless floods, refreshing the Cliff-Gila valley, which accommodates the biggest intact bosque habitat within the Decrease Colorado River Basin. The valley is house to the biggest focus of non-colonial breeding birds in North America. The river can be a stronghold for threatened and endangered species, corresponding to nesting yellow-billed cuckoos, the Gila chub, Chiricahua leopard frogs and Mexican garter snakes all stay there.

At odds with efforts to maintain the Gila wild are plans by a bunch of roughly 200 long-time irrigators in southwestern New Mexico. Every summer season they divert water from the Gila to flood-irrigate pastures, which de-waters stretches of the river. The irrigators have been making an attempt to lift cash to construct impoundments to take much more of their share of water, however up to now have been unsuccessful, partially due to opposition from conservation teams.

Extreme drought this spring mixed with water overuse resulted within the drying of the Gila River in jap Arizona and the dying of the fish inhabitants.

Cattle are one other risk to the river’s organic integrity right here — each unfenced home cattle and feral cows. Cattle break down riverbanks, widen the stream and lift water temperatures. They eat and trample riparian vegetation, inflicting mud and silt to choke the circulation, and destroy habitat for endangered species. The Heart for Organic Variety just lately sued the U.S. Forest Service to pressure the company to take motion.

“We’re in a cow apocalypse,” mentioned Todd Schulke, a founding father of the Heart for Organic Variety. “They’re even within the recovered Gila River habitat. It’s simply heartbreaking.”

Because the river enters Arizona, the riparian ecology stays largely intact, particularly within the 23 miles of the Gila Field Nationwide Riparian Space. Right here, 23,000 acres of bosque habitat is in full expression, with thick stands of cottonwoods, velvet mesquite bushes and sandy seashores. It’s one in every of solely two nationwide riparian areas within the nation put aside for its excellent biodiversity; the opposite is on the San Pedro River.

Because the river leaves the riparian space, it undergoes a hanging change: large cotton farms close to the cities of Safford, Pima, and Thatcher, first planted within the Nineteen Thirties, cowl the panorama. The dried, brown stalks of harvested cotton crops stand in a area, bits of fluff on prime. Rising cotton within the desert — which makes use of six occasions as a lot water as lettuce — has lengthy been seen as folly by critics, made doable solely by hefty federal subsidies.

Farmers in Safford, Arizona pump groundwater close to the Gila River to irrigate their fields.

A lot of the flood pulse ecology is misplaced right here, because the river is diverted or topic to groundwater pumping. As an alternative of flooding, the river cuts deeper into its channel, reducing the water desk, which many crops can not attain. The cottonwood stands and different riparian habitats have disappeared. “You need the groundwater inside 5 ft of the bottom, but it surely’s largely 8 to 12 ft,” mentioned Melanie Tluczek, govt director of the Gila Watershed Partnership, which has been doing restoration right here since 2014.

It’s a harsh place for brand spanking new planting. The river is dry in lengthy stretches. Tamarisk, a pernicious invasive tree also called salt cedar, must be lower down and its stumps poisoned to forestall regrowth. Small willows and Fremont cottonwoods have been planted on barren desert floor. Wire cages over toddler bushes preserve elk, beaver and rabbits from gobbling them up.

In the meantime, tamarisk grows prolifically, slurping up water, altering soil chemistry and the character of flooding, robustly outcompeting natives, and rising the danger of wildfire.

“If you are able to do restoration right here, you are able to do it wherever,” Tluczek mentioned. She mentioned the Gila Watershed Partnership has eliminated 216 acres of tamarisk alongside the river and planted 90 acres with new native bushes. However the Gila right here won’t ever appear to be it did. “We are able to’t restore the previous,” Tluczek mentioned. “We’re going to see a floodplain that has extra dryland species and fewer floodplain species.”

The Coolidge Dam in Arizona kinds the San Carlos Reservoir, which is now at historic lows.

Downstream, the Coolidge Dam kinds an enormous concrete plug on the Gila. Constructed within the Nineteen Twenties by the federal authorities, it was the results of irrational exuberance in regards to the quantity of water on the Gila and meant to produce farmers with water. As we speak, nevertheless, the reservoir is often dry. Constructed to carry 19,500 acres of water, this yr the water within the lake lined simply 50 acres.

From right here to Phoenix and on to the Colorado, water solely often flows within the Gila. But even the small quantity of water that continues to be is significant to wildlife. “The place there was water close to the floor, animals scent it and can dig down within the sand within the riverbed to free it up,” Wilbor mentioned. “You arrange a digital camera and it’s like an African watering gap, with species after species taking turns to return use the water.”

Will the Gila River by way of most of Arizona to the Colorado ever be restored to a semblance of the organic jewel it as soon as was? The possibilities are slim. However two pioneering efforts have introduced again parts of the desiccated river.

In 2010, Phoenix accomplished a $100 million, eight-mile restoration of the long-dewatered Salt River the place it joins the Gila and Agua Fria rivers at Tres Rios. Fed by water from town’s sewage therapy plant throughout the highway, this constructed complicated consists of 128 acres of wetlands, 38 acres of riparian hall, and 134 acres of open water. It’s thick with cattails and different vegetation, an island of inexperienced round a lake amid the sere surrounding desert.

Ramona and Terry Button run Ramona Farms on the Gila River Indian Group, the place some water allotted to the tribe is being launched into the Gila.

On the close by Gila River Indian Group, in the meantime, house to the Pima — or the title they like, Akimel O’othham, the river folks — is one thing referred to as a managed space recharge. The Akimel O’othham, who share their group with the Maricopa, are believed to be the descendants of the Hohokam, an historical agricultural civilization with an unlimited community of irrigation canals that was largely deserted centuries in the past. The Akimel O’othham continued to farm alongside the Gila in historic occasions till their water was stolen from them within the late 19th century by settlers who dug a canal in entrance of the reservation and drained it away.

After a century of the Akimel O’othham combating for his or her water rights, in 2004 the Arizona Water Settlement Act supplied the tribe with the biggest share of Colorado River water from the Central Arizona Mission, a share bigger than town of Phoenix’s allotment. The tribe is now water-rich, utilizing a lot of that water to revive its tribal agricultural previous, although with fashionable crops and strategies.

Final yr, among the Colorado River water was launched into the Gila to be saved in an underground aquifer and used to create a wetland.

Each of those initiatives, at Tres Rios and on the reservation, have created oases in a harsh desert panorama, bringing again an array of birds and wildlife, and — within the case of the Akimel O’othham — serving to revitalize the cultural traditions of those river folks.

“We’re not going to have rivers with native species within the Southwest until we will defend and restore these methods,” particularly with a altering local weather, Siwik mentioned. “Defending the perfect, restoring the remainder — or else we lose these methods that we want for our survival.”

CLICK IMAGES TO LAUNCH GALLERY

Reporting for this text was supported by a grant from The Water Desk, an initiative primarily based on the College of Colorado Boulder’s Heart for Environmental Journalism.